“Like A Person Enjoying Singing in the Shower”

An Interview with Deepak Chopra

In half the spiritual world, the term “abundance consciousness” elicits an allergic reaction, but in others it evokes an aspiration to a richer life, materially and spiritually. One of the priests of abundance consciousness is Deepak Chopra, a physician by training who has become a spiritual advisor to celebrities and business people. We sent Igal Harmelin Moria to find out from him how spirituality is connected to money and abundance.

Deepak Chopra is one of the world’s most famous people. The media likes to call him “guru”, but, as a well-known Israeli song says, “he did not know that about himself at all:” he defines himself as an explorer of reality who loves sharing his insights with others. As a physician by training, he is one of the most prominent voices in the field of alternative medicine and has written many books about the body, the mind and the connection between them. This is why I wanted to interview him for a previous issue of “Chayim Acherim”, which was dedicated to the body. When I proposed it to the magazine’s editor, Chava Rimon, she shot from the hip: “Chopra? We should interview Chopra for the money issue. Chopra knows how to make money.” It was not meant as a compliment.

I have known Chopra for many years. We were both among the closer students of the Indian Guru, Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. Full disclosure: I like Deepak a lot, even if I have not read most of his books and I have some questions regarding certain aspects of his philosophy. I like him because of who he is: a warm man with a brilliant intellect who makes a captivating conversation partner. Many famous people, some even much less famous than he, are very full of themselves and talk down to you; but not Chopra.

[The following is a translation of an article that I wrote in Hebrew for the October 2019 issue of the Israeli monthly Chayim Acherim. The issue was dedicated To money and spirituality. A PDF of the original Hebrew article can be viewed here.]

Talking to him one-on-one, he reminds me of a kind family doctor who is interested in creating a genuine human connection with you, as well as a good high school friend who eagerly and passionately shares with you an idea he had or a book he has just discovered. There is also something of an artist in him, who deeply enjoys the beauty of his creation and is eager for you to enjoy it as well, even if he does so lightly and with plenty of humor. Above all, I respect and appreciate the fact that he spends his life thinking deeply about life’s big questions

Chopra received by the Dalai Lama in Dharamshala. Photo: Office of Tibet

Of course, Chopra has no need to for my liking or my appreciation. Famous people from all over the world are happy to spend time with him, get some advice or even exchange a word or two. People like Oprah Winfrey, Lady Gaga, as well as leading scientists, philosophers, artists, and business people– many are eager to rub shoulders with him. Like every famous person, he also has his share of opponents, including those who dismiss him as a charismatic charlatan. One must admit that he does have plenty of charisma. In Greek, charisma means gift, in the sense of a gift from the gods. If that gift was meted out in goblets, Chopra received a whole bucket. Personally, I am convinced that he is no charlatan. Every time I meet him, I am impressed with his curiosity, his simplicity and his almost childlike passion. He never stops inquiring and learning.

So yes, Chopra is a wealthy man. He earned his wealth honestly by working as a physician, by earning royalties from the sale of his books and by offering lecturing and seminars around the world. In 2014, a journalist from San Diego estimated his wealth to be 80 million dollars. I am curious why so many people make mention of his wealth, but not positively. When my wife and I watched one of Paul Simon’s last concerts, his enormous wealth did not prevent us from enjoying his music. Business students reverently study the biographies of people who have amassed wealth, including those who are questioned around the morality of their actions or the sources of their wealth. But when it comes to spirituality, being wealthy is a stigma.

Of course, part of the problem is that quite a few gurus have taken advantage of their disciples in order to enrich themselves. But as I said, Chopra is not a guru: he never invited anyone to be his “disciple” or a “student”. A few years ago he invited me to sit in one of the lectures that he delivered as part of a workshop he was conducting for a few hundred participants at the Kripalu Yoga Center in Western Massachusetts. When we met in his room, right after the lecture, he turned to me and said, almost apologetically: “Did you see what was going on there? These people are writing down every word I utter!”

Another part of the problem is that many of us hold an ambivalent attitude towards money, even if it is not always conscious. Psychologists have many theories about it, but Christianity had a role to play in this, not to mention Communism. As a result, we tend to believe that spirituality and wealth cannot occupy the same space, and that the spirituality of a wealthy person is flawed. Does this mean that difficulty in paying your monthly bills is a pre-requisite to authentic spirituality? Why should we not compensate people who engage with spirituality in the same way that we compensate artists, athletes, entertainers or scientists? It’s just a matter of priorities.

Up to Date

We met in the beautiful studio of Ghiora Aharoni, an Israeli-born New-York artist. It has been about a decade since I last met Chopra, and both our heads have turned grey. But just like in the old days, he is energetic, eloquent and full of passion, even if he seems a bit more sedate. (He is, after all, 73 and besides, he has nothing left to prove.)

His dress has become more free, bold and playful. In the past he wore suits and ties. He showed up at our meeting dressed in a chic and elegant blend of East and West: a sleeveless jacket with golden buttons and a Nehru collar, whose gray color matched his fashionable jeans and the red accents on the edge of its pockets and collar matched his black-and-red sneakers. Add to that his bright orange, Nehru-collared shirt and the designer glasses he has been wearing for the last few years, and you get someone who knows he is a star and dresses accordingly.

With Chopra you don’t need warm-ups. He is immediately available, immediately intimate, as if we had met the day before. After about 15 minutes of “who of our old friends are you still in touch with” and such, I ask him to talk about money. As soon as he starts answering, I am reminded why he is such a star: it does not matter what you ask Chopra about, he answers immediately, without hesitation, as if plugged in to an encyclopedic storehouse of knowledge in his awareness. He speaks in complete paragraphs which, with some editing, could been made into chapters of books. No wonder he has authored more than 40 books! Moreover, however specific and focused your question is, he will attempt to answer it from the widest possible context, which might include the history of the universe, the evolution of human consciousness, and even God.

“No one knows where the idea of money came from” he says. “From Yuval Noah Harari’s books I’ve learned, that eight species of humanoids – human-like creatures – lived before us. Up to about 60,000 years ago we, the homo sapiens, were not that different from them; but then what he calls ‘cognitive evolution’ started in human consciousness: we started telling stories.”

Up to that point, according to Harari (as transmitted by Chopra), we lived in packs of 100 people at the most; but the availability of language removed that barrier. “Once language developed, we could tell stories and through these, leaders could gather around them increasingly larger groups”, he explains. “The more complex the story, the larger was the group that the leader could gather around him. When a group is not larger than 100, everything can be based on bartering. For example: you will keep an eye on my children and I will make you a leather garment or something like that. But once society became more complex, standards of commerce had to be established. It started with a certain kind of shells, and then evolved to small lumps of precious metals, coins, I.O.U.s, and the bills that we use today. From there, money developed into credit cards and now, in the digital world, money is just a combination of zeroes and ones in some server farms.” His point: money is an idea, a story, a means of expressing the way we value things that are important to us. Money lives in our consciousness.

Singing for fun in the shower

Relating to money as an idea in our consciousness is not unique to Chopra and is not new, although Chopra takes this standpoint towards matter in general. He expounds a current, modern-day version of the ancient philosophical teaching known as Advaita Vedanta. According to this theory, the unity of consciousness—not the consciousness of the personal ego but the cosmic, universal, trans-personal consciousness—is the ultimate reality and the entire world of diversity, all forms and phenomena, are its expressions.

According to this teaching, the way we perceive the world as well as our ideas about the nature of reality are aspects of this sea of consciousness. These often unexamined ideas are based on social/cultural/psychological conditioning. This includes our ideas about our material world. According to Chopra, our belief that these ideas reflect objective truth is what fixes our reality and strengthens our beliefs, thus limiting us and our actions. (Watch, for example, his take on “The Superstition of Matter.”)

As I said, these ideas are not new. Even the founders of Hassidism embraced them: as far as they were concerned, there is only one reality, expressed in the Biblical verse “the Earth is full of His Glory” (Isaiah 6:3). Or as the Zohar, the quintessential text of the Kabbalah, says: “There is no place where He is not” (Tikkunei Zohar57): everything we see around us or with our mind’s eye are garments of the One. But Chopra thinks as a physician; when physicians learn about new discoveries in science they seek to implement them so as to improve the health of their patients. Chopra uses this format for interacting with his readers and listeners: if everything is ultimately consciousness and our consciousness determines our reality, how can he help his audience change their consciousness?

These ideas apply to money as well. If money is an idea in our consciousness, changing our attitude towards money, which stems from conditioning and habits, is a necessary condition, he believes, for changing our financial situation. How do you change such habits? According to him, psychological studies indicated that only 21 days are needed for changing habits. Accordingly, he created the “Chopra Abundance Challenge – 21 Days of Meditation for Wealth and Well-Being”—21 guided meditations aimed at changing our attitude towards money. It is sold in a number of places on the internet, although there are a number of sites where these meditations are offered free of charge (e.g. here).

As part of my preparations for this article I responded to the challenge—short guided meditations using familiar Sanskrit mantras (such as Aham Brahmasmi – I am Brahman, the totality) voiced by Chopra as well as short writing exercises. At the end of three weeks of practice, my coffers did not miraculously fill up with gold, but the program challenged me to examine my relationship to money and I found it useful.

One of the criticisms that can be heard about Chopra’s self-improvement programs, including those that are offered for free, is that they are suitable only for people who already have money. Those who struggle to pay their bills or experience an uphill battle to feed their families will not be able to derive much benefit from this information. The diagnosis is correct, but the criticism is not in place: Chopra never claimed to bring salvation to the world’s poor. As he puts it, “I’m like a person singing for fun in the shower, who discovers that his neighbors enjoy his singing and ask him to record it. To his great surprise, his recording becomes a best seller.” The people who are attracted to Chopra’s “singing” are those who discovered that material affluence, in-and-of-itself, cannot bring the satisfaction they are seeking and then find his teachings useful. Good for him and good for them!

His philanthropic contribution to society is done through the Chopra Foundation, an organization aimed at supporting research on, and application of, alternative programs for improving health, those that don’t relate to the body as a machine in need of repair but rather as a dynamic whole which is meant to serve as a vessel for the expression of consciousness. He collaborates with various organizations, medical schools among them, in order to support such programs. Once a year, his foundation assembles a Sages and Scientists Symposium, aimed at integrating the science of consciousness with modern research.

With Jane Goodall

The difficulty I have with Chopra’s teaching is that it sometimes sounds too simple, even simplistic. Like our former guru, Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, he has a genius for spreading easily digestible versions of deep spiritual teachings, the assimilation of which demands a considerable degree of nuanced thinking. This simplicity may be misleading. On the other hand, it may provide a low entry bar for many who, without such an introduction, would have not entered the spiritual life. As for Chopra himself, he is anything but simplistic.

Teaches How to Fashion Stories

Let’s get back to the wealthy. Giant corporations (such as JP Morgan and Gallup) are using Chopra as a consultant for their top management, and probably pay him handsomely for his advice. What does he offer them? “Take any well-known company you like” he tells me: “Apple, Amazon, McDonalds. What they sell us, primarily, is not a product or service, but a story.” He brings the story that Starbucks sells as an example: where the coffee is from, who are the growers who benefit from the sale, how the coffee was raised in a way that benefits the environment, etc.

Chopra examines with business people what their story is. “When I meet company directors,” he tells me, “first of all, I ask them seven basic questions:

Who are you? How would you define yourself? In most cases they have a hard time with this question. They can’t even tell you who they are. And these are business leaders!

What do you want? What do you want for yourself? What do you want for your community? What do you want for the company that you are at the helm of? And if you have aspirations for the whole world, what are they?

What is your purpose? Why do you do what you do in the end? Let’s say that the person answers, ‘I want to make a lot of money.’ Why? Because you want to be happy? So your goal is happiness, then. But there are many ways to achieve happiness that don’t have anything to do with money. So if being happy is your goal, we have to think of other ways to bring about happiness to you.

What are you grateful for? This is a very important question because the moment you experience gratitude, you are already in abundance consciousness. I never ask a person whether he or she feels grateful. I ask them to just close the eyes and ask themselves what they are grateful for. Once you are grateful, you cannot feel hostility. You cannot feel anger. You cannot feel resentments or grievances when you count your blessings.

What place do you have for meaningful relationship in your life? Both in your business life as well as with your family and friends. How do you contribute to a meaningful relationship?

Are there any heroes or heroines that you admire? These can be mythological heroes, historical heroes or business heroes. If Bill Gates is your hero – why?

What are your unique strengths and talents? How do you express them and who benefits?

“Once they answer all these question we start working on their story. I start by asking them about their back story, their past, because that back story influences the present one. The next question is, what is your present story? And finally: where does all this lead to? Where are you going?

“At the end of this process”, he summarizes, “after they see the full picture from the top of the mountain, I ask them to think how to bring it down to the foot of the mountain, to share it with others in their organization. And I ask them to make it a love story. Because you know, a story without heroes, villains, emotions, is a boring story…. So yes, we’re talking about a movie. We all live in a movie. The question is how to improve this movie.”

Boycott By TED

Two days before meeting Chopra, my editor, who knows I like him (and generally believes that I am too positive of a person) made sure to send me a copy of an article written in the Israeli daily Ha’aretz two years ago by Rogel Alpert, one of the paper’s senior writers. The article appeared after Alpert attended a lecture delivered by Chopra to a crowd of 4,000 at the Menorah-Mivtahim arena in Tel Aviv. The title of the article summarized the writer’s impression: “Who Needs Facts When We Have Deepak Chopra.” According to Alpert, Chopra is just a shrewd businessman.

With the Queen of Media, Oprah Winfrey. Photo: Felicia Angel

I asked Chopra how such criticisms make him feel. “When I started, such articles would have offended me a lot. Today I don’t get too excited when someone doubts my spirituality because I am materially prosperous.” Making money, he claims, was never his goal. “I started as a doctor. Very early it was clear to me that the mechanistic approach does not work, so I started exploring and applying mind-body medicine. The next step was integrative medicine, that is, to examine the patient’s lifestyle: do they eat and breathe well? Do they sleep well? Does he/she have a way of releasing stress and tension?

“I soon recognized that this was not enough either, that neither of these approaches confronts us with the bigger questions: What is the reason for human suffering? What is identity? What is birth and what is death? What is the soul? Does God exist? These are questions that all the great traditions invite us to inquire after and that modern science and modern medicine don’t touch. The need to confront these questions is not a philosophical but an existential one. So I started writing about all these things and soon I found that many found my writings useful.”

It’s not clear to him why people have issues with his material prosperity. “Look how the health industry operates nowadays: for every member of Congress in Washington, D.C. there are 28 lobbyists from health-related companies (pharmaceuticals, medical equipment manufacturers, etc.). Lobbyists are people who are paid in order to tilt the health policy in such a way as to benefit the interest groups that sent them. So why do I have to apologize for helping people and organizations who approach me from their own free will, not as part of this trading floor?”

As far as he is concerned, his approach is the ideal way to earn one’s living as a doctor. “If the human race manages to lives through the environmental crisis that we are in the midst of”, he says, “and if we are able to base our society on much healthier principles, then what I do now will be the way to earn a living: helping the physical, emotional, mental and spiritual health of individuals and organizations.”

Chopra does not relate to all criticisms with the same equanimity. He has an ongoing, well-publicized conflict with the world-renown scientist Richard Dawkins, who is not only a confirmed atheist but combats any expression of religious thinking and belief with the same zeal that religious fanatics fight modernity. Dawkins got Chopra’s blood boiling when, in 2002, he lectured about “militant atheism” at a TED conference. He invited the audience to combat any expression of religiosity (which he equated with ignorance) and to donate to a fund that he established for this purpose. He called upon his listeners to no longer be “polite and respectful” towards religion, which he sees as the root of all of ill in the world.

Chopra, who was scheduled to lecture after Dawkins and speak on creativity, decided to respond to Dawkins’ invitation to do away with politeness and respect and fought back. He accused Dawkins of anti-religious bigotry and hypocrisy, and said that Dawkins was using his fame as a scientist from Oxford to promote an ideological campaign that has nothing to do with science. This bold response cost Chopra his relationship with TED, where he is now banned. The video of Chopra’s response was removed from TED’s site.

This is a battle between two axioms, two fundamental assumptions. Science’s axiom is that matter is the ultimate reality, and that consciousness, emotions, thoughts (including spiritual experiences and religious feelings) are by-products of the actions of our nervous system. The spiritual-religious axiom assumes the opposite: the ultimate reality is beyond matter, imperceptible to the senses and ungraspable by our thoughts – call it Mystery, God, Being, what have you – and the material world is an expression of that level of intelligence.

But a fundamental assumption is, in the end, just that: an assumption. And the insistence that only one of these two is right is, by definition, fanaticism. Indeed, Dawkins’ militant anti-religious stand received scathing criticism not only from religious circles, but also from quite a few of his scientist colleagues, including those who profess to be atheists, who claimed that he stepped outside the bounds of science. Chopra’s stand is that the insistence that the material axiom as the sole truth prevents us from grasping the totality of the entity that we call “human” and to develop our potential.

Going for Broke

I believe that this is Chopra’s uniqueness: beyond the personal charm, the eloquence, the encyclopedic knowledge, he respects these two axioms as complementary and sees them as valid, each in its domain. He weaves the best of these two axioms into a very personal teachings which has one goal in mind: improving his listener’s lives. I feel that more than anywhere, this is expressed in his new book, Metahuman, which will be published in English when this issue goes to press.

In the book, Chopra “goes for broke,” as he puts it: he integrates everything he has learned, taught, lectured and written into a great symphony of self-discovery. He leads his readers to acknowledge that the “reality” what we observe is no different, in principle, from virtual reality; beyond this illusion, which he offers ways of piercing through, lies the infinite human potential in all its glory.

Chopra’s new book

He does not pretend to be the first teaching this. But he does it in his unique manner: the book is very readable, uses contemporary terminology and backs up the ideas and insights that he shares both with the help of current scientific thinking as well as with the insights of the ancient traditions of knowledge. In the typical Chopra manner, he ends the book with a “DIY” program of 31 days, which can help the reader to start implementing these ideas in their lives.

What will the scientists say? When Chopra’s personal assistant sent me the book to review, she attached ten pages of words of praise about the book from thirty writers, almost all of them prominent scientists, most of whom are well-known in the world of academia. And about people from spiritual circles? In Ken Wilber’s words: “Metahuman is a wonderful explanation—and exploration—of the very highest and ultimate potentials that human beings possess….[If you would like to know how to actualize this potential],Metahuman is a terrific place to begin!”

Chopra, Maharishi and the Beatles

The following is a special section added to the interview with Deepak Chopra.

As I said above, Chopra and I share a common past: we were both students of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, founder of Transcendental Meditation and one of the most influential teachers in the second half of the twentieth century. Although both of us eventually broke with him and with his organization, we both consider the years in which we were part of his closer circle a rare privilege. In Chopra’s case, this relationship, as well as its ending, had far-reaching implications.

A little background: Chopra comes from a highly respected family of physicians in New Delhi. His father was a famous cardiologist who, before Indian independence, was the chief medical advisor of Lord Mountbatten, the British Viceroy of India. Young Chopra arrived in the United States in 1970 with his wife, not long after finishing his medical studies in India. The Vietnam War was raging, and American hospitals were losing young doctors to the draft. Physicians from all over the world received work visas for America in order to make up for the shortage, often being paid very low salaries. Chopra worked dayandnight as an emergency physician, and after some years started specializing in endocrinology.

By the 80’s he had a thriving endocrinology clinic in Boston. Personally, however, he was stressed and smoking too much. He took a course in Transcendental Meditation and with the help of the practice was able to quit smoking and feel relief. Before long he was prescribing TM to his patients.

In 1984, when Maharishi came for a visit to Washington, D.C., Chopra and his wife flew in from Boston in order to sit in on one of his talks. When it was time to leave for the airport in order to catch the flight home, they left the hall through one of the back exits. Maharishi noticed that they had left and cut his lecture short. He left through a front exit, reaching the lobby exactly when the Chopras arrived there. “Let’s go up to my suite and talk” he said to them. When Chopra tried to explain that they were in hurry to catch their flight, Maharishi said smilingly, “Don’t worry, there will be many more flights to Boston tonight.”

As Chopra soon learned, it was difficult to resist Maharishi’s charm. Changing the flight was only the first course: within moments of the couple’s arrival at his suite, Maharishi invited Chopra to drop out of his clinic and work with him. His wife panicked: “We have two children—how will we support ourselves?” “Don’t worry,” Maharishi tried to calm her, “you will have more than enough.”

Hard as Maharishi tried, the Chopras politely rejected the offer. But on the flight back home, Chopra felt that he had made a huge mistake. The moment they landed in Boston, he called Maharishi to say that he changed his mind and that he was coming back to Washington.

Chopra’s life trajectory took a sharp turn as a result of this jump into the unknown. Maharishi’s movement’s experienced and well-oiled publicity team got mobilized and within a short time, Chopra’s books made it to the New York Times best-seller list and he often appeared as guest in the most popular TV programs. Superstars sought out his company and before long he was one of the bestknown celebrities in America. He also became the crown jewel of Maharishi and his movement.

The bond of trust and love between Chopra and Maharishi reached its climax in 1990, when Maharishi became very sick in India. He was believed to have been poisoned. Chopra’s father attended to Maharishi in Delhi while Chopra himself flew in from Chicago and organized for Maharishi to be flown in to London for medical treatment. Upon arrival at the London hospital, Maharishi was clinically dead, and Chopra revived him. Soon he recovered, in a speed that surprised his physicians and nurses. For months, Chopra stayed with him around the clock and attended to his health needs.

Maharishi’s illness was kept hush-hush: officially, most of us were told that Maharishi was in silence. The whole time he stayed in a house in the South of England, with only Chopra and a few Indian helpers by his side. In addition to attending to Maharishi, Chopra took long walks with him in which they were discussing various topics, particularly the Vedanta aspect of Indian philosophy. To this very day, Chopra’s teaching is based on things he learned from Maharishi during those days. When Maharishi recuperated, Chopra returned to the US to continue touring, lecturing and writing while Maharishi moved to his ashram to the Netherlands, where he stayed until his death in 2008.

The idyllic relationship between Chopra and Maharishi ultimately came to an end, after almost 10 years. According to Chopra, Maharishi accused him of trying to compete with him and demanded that Chopra stop writing books and come to live with him at his ashram in the Netherlands. Chopra refused and went his own way. By the looks of it, disconnecting from Maharishi has done Chopra good: in 1993 he appeared on the TV program of the communication queen, Oprah Winfrey, and since then his popularity has been constantly increasing.

Maharishi felt betrayed, and it’s easy to see why: as far as he was concerned, the satellite which he launched into space has taken an independent course. Once Chopra was interviewed by Oprah and it was clear that he was going his own way, all of Maharishi’s Transcendental Meditation centers were told not to have any contact with Chopra and to no longer distribute his books. Chopra became the one “whose name is not to be mentioned.” (Read Chopra’s account here).

The Mysterious Visit

During the years that this drama unfolded I was living with Maharishi at his ashram in The Netherlands. It was a large, red-brick, 4-story structure which had served as a Franciscan monastery before it was purchased by the Maharishi’s organization.

One day, in the Fall of 1991, all the ashram’s residents were told by Maharishi’s secretaries that Maharishi’s quarters, and the halls leading to them, were strictly off limit to us for a few hours. A guest was coming, whose identity was supposed to be kept confidential. It was hard to keep the secret: within days we found out that the guest was no other than George Harrison, of the Beatles, and that Deepak Chopra had brought him to visit Maharishi.

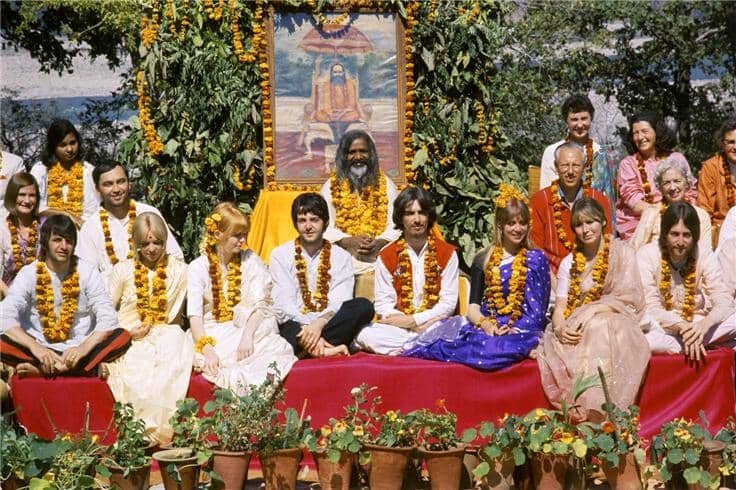

This was a big deal for us. When the Beatles adopted the practice of Transcendental Meditation in the late 60’s and went to India to spend some time with Maharishi at his Rishikesh ashram, it created a media storm. The Beatles were at the height of their popularity and, as a result, the whole world was exposed to the smiling image of the Indian monk. Other celebrities crowded the ashram at that time, including the Beach Boys, Donovan, and the actress Mia Farrow who arrived there joined by her younger sister, Prudence (for whom the Beatles’ White Album song “Dear Prudence” was composed).

Maharishi’s Ashram in India, 1967. The Beatles and their wives are sitting in the front row.

But this love story also ended bitterly: the Beatles left the ashram all of a sudden, with John Lennon accusing Maharishi of having tried to sexually assault Mia Farrow. The Beatles being the Beatles, these rumors never left Maharishi.

Maharishi himself never responded to the allegations. For years, when journalists would ask him about the Beatles’ allegations, he would respond by inquiring: “How are they? Are they still producing good music?” He seemed to be unfased by the rumors. We, his closer students, had no doubt that he was truly a monk. For many of us the Beatles’ music was part of the formative years, and so that discord was uncomfortable, to say the least. George Harrison’s visit provided some kind of vindication, even though we did not know what had happened in the meeting.

Before the dust had a chance to settle, a few days later, while shopping in the small village not far from our ashram, the owner of the flower shop told us excitedly that on the previous day, none other than Paul McCartney walked into his store and asked him to make a bouquet for Maharishi, whom he was about to meet. Our jaws dropped: What’s going on? Will Ringo come next? No, Ringo never came. But a few months later, George Harrison appeared at a concert in the Royal Albert Hall in London, his first public concert in 23 years. The concert was announced as a benefit for one of Maharishi’s campaigns. In the last two songs, Ringo came on stage to accompany George on drums. Years later, after George’s death, Ringo and Paul took part in a concert to benefit a foundation that offers courses in Transcendental Meditation.

The content of the meeting between Harrison and Maharishi was surprisingly revealed years later, in 2006. Chopra was invited to be a guest editor in the Indian daily Times of India. He took the opportunity to tell about the meeting and what happened there. Among other things, Harrison told Maharishi, “I came to apologize.” “Apologize for what?” asked Maharishi. “You know for what,” answered Harrison.

The Chopra and Harrison families went on vacation together in the early nineties. From Deepak Chopra’s private photo collection.

Maharishi asked, “Tell Deepak what happened there.” Turning to Chopra, Harrison said that Maharishi had asked them to leave because he forbade the use of drugs, and he found out that they had continued using drugs in the ashram. John Lennon, who saw in Maharishi a father figure, was deeply hurt and responded angrily and bitterly. Harrison was asking Maharishi for forgiveness because he knew the truth but did not defend Maharishi. He was also the only person who could have done so: the two other Beatles, Ringo and Paul, had left the ashram by then.

Like all news concerning the Beatles, this one went viral (before “going viral” was a thing). Some suspected that Chopra invented the story in order to defend his guru, except that in 2006 Chopra was no longer connected to Maharishi and had no investment in protecting him. Furthermore, Chopra also claims that in the years when he was still connected with Maharishi, Mia Farrow asked him to convey her love to Maharishi.

I later discovered, that in page 285 of The Beatles’ Anthology, George is quoted as saying: “Someone started the nasty rumor about Maharishi, a rumor that swept the media for years…. It’s probably even in the history books that Maharishi ‘tried to attack Mia Farrow’ – but it’s bullshit, total bullshit. Just go and ask Mia Farrow.”